Training Load and Performance

I come from a medical background. Medical science has an evidence base from clinical studies that typically involve thousands of randomly selected patients. Sport science is rather different as the subjects are not representative of the whole population and sample sizes typically run into a mere handful of athletes. We have to be wary of model curves with good yet statistically and practically insignificant correlations to experimental data.

We have discussed individual training sessions and the use of training zones referenced to some correlate of lactate threshold. We will now look at the effect of multiple sessions of training on our performance. The ultimate goal is to perform well at some competition or series of competitions. Modeling performance in this way may guide us in our training both to perform well and to avoid over-training and injury.

Typical models consists of two parts:

- The first part is the calculation of the training load arising from a single episode of training. It is represented by a single value. Examples include RPE, TRIMP, RSS and TSS.

- The second part uses the training load values from successive workouts to predict performance. Typically this is expressed as some function of fitness and fatigue where fitness and fatigue are calculated from all the training loads and when they happened. The output of such models is in reality a guide with no concrete way of determining that they are "correct" in value or form. There is evidence however that they are of value.

One scheme might simply be to subtract fatigue from fitness:

| performance = fitness(loading) - fatigue(loading) |

Whatever the form of the performance function takes, it needs to have passed a series of all load and time value pairs. The very first step therefore is to calculate training load. This is not straightforward and many of the proposed equations seem to be rather ad-hoc.

Training Load Scores

How does a single workout affect us? What training load has accrued. Unfortunately this is not easy to say exactly. In fact it is hard to say exactly what training load is.

- We know that one athletes hard is another's easy.

- We know that as we get fitter the same level of activity gets easier.

- We also know that running a bit faster or generating a bit more power feels quite a bit harder and is quite a bit more fatiguing.

- We know that the longer the episode of training the more fatigued we get.

A score of training load should take all these factors into account.

The changes brought about by training are complex. Several things are consumed, produced, lost, eliminated then replaced over varying periods of time e.g. ATP, CP, glucose, glycogen, fat, heat, water, CO2 and lactate. Microscopic damage occurs which might degrade our performance in the short term but that then stimulates adaptation and improvement in the long run. It is difficult to conceive of a single value that could somehow represent the complexity of these changes.

Rate of Perceived Exertion RPE

This is the oldest way of assessing training load. Typically an increasing score (e.g. Borg Scale) is assigned an increasing intensity number. This intensity number is then raised to a power to reflect that greater work intensities are a lot more fatiguing. When multiplied by time this gives a relative measure or workload. Although a little rule of thumb, such simple ways of assessment are of value. The ready availability of the means to measure and record various physiological parameters have however lead to methods based on these that have largely superseded subjective assessment. One advantage of this is it automates the process as we do not have to enter our perception of how hard a workout was afterwards.

Training Impulse - TRIMP

One of the earliest non-subjective assessment of training load was developed by Prof. Eric W Bannister in 1990. He called it Training Impulse or TRIMP. TRIMP is a calculated value based on the proportion of cardiac reserve (Karvonen) obtained during a workout. If we call the proportion of heart rate reserve:

| Phrr | = |

|

then

| TRIMP | = | t | × | Phrr | × | 0.64 | × | e(𝝀 × Phrr) |

TRIMP

where t is the time in minutes. The initial step to deriving this formula was to simply make TRIMP proportional to the product of time and Phrr but this did not reflect the perceived much higher load with high Phrr and so an exponential factor was added. Although the average HRexercise is shown, these days we would summate lots of little TRIMPS over the duration of the workout. The general form of this equation seems right with an increasing slope of workload vs. Phrr. The exponential factor was designed to correlate with measured blood lactate levels. A strange attribute of this exponential factor is that the constant factor in the exponent differs between men and women. This means a male athlete would accrue a greater TRIMP when working at some Phrr than a female athlete at the same intensity. As there is no confidence interval stated for these factors we should be wary of this conclusion. It is also important to note that being based on heart rate the formula has to compensate for the squishing up of dynamic range as we approach maximum heart rate and so will not be applicable to other intensity measures such as flat pace or power. We should expect such formulae to have a different form.

To give a feel for this, say we have a male and a female athlete both with a resting hr of 60 and a maximum hr of 200. If he exercises with an average hr of 165 for 60 minutes then:

| TRIMP = 60 × 0.75 × 0.64 × e(1.92 × 0.75) = 122 |

If she exercises with an average hr of 110 for 60 minutes then:

| 60 | × | 0.5 | × | 0.64 | × | e(1.67 × 0.5) | = | 44 |

Running Stress Score - RSS (Stryd)

RSSStryd states that their running stress score has the form RSS = 100 × training duration × (Power/CP) ^ K though the value of K is not stated. This seems incorrect but a reasonable (if imperfect) fit is given by:

| RSS/min = 2/3 × PN + PN 4.9 |

Again the general form (upward curve) seems intuitively correct. The exponent of 4.9 is much greater than that used for a cycling power TSS which for a steady effort is 2. This is supposed to reflect the increasing workload of running with increasing pace.

Training Stress Score - TSS

The official definitions of TSS in my opinion hide its simplicity. It can be shown to be equivalent to:

| TSS | = |

|

× | RMS(P2) |

The idea behind using RMS is to account for a perception of additional workload where power is not constant but varies. Although widely used there are problems with this calculation of training stress. It does not produce a higher workload for a rapidly varying power output when compared to a slowly varying power output of the same amplitude of variation and mean power. The sum of the calculated TSS scores from two consecutive workouts does not equal the TSS of the two workouts taken together. Although it has been shown to be useful it cannot be optimal.

Excess Post-exercise Oxygen Consumption - EPOC

As we would expect, the rate of oxygen consumption (VO2) is increased during a training activity compared to that at rest. But what happens after exercise? It has been shown that it does not return immediately to the pre-exercise level as we might have expected. Instead it is increased and this increase slowly decays over time. The area above the pre and post VO2 curves is the Excess Post-exercise Oxygen Consumption (EPOC). This value represents the oxygen required to restore the pre-exercise levels of the metabolites described above and also repair damage which is also an energy consuming process that requires oxygen. This return to a desired optimal state is a general fundamental physiological principle (homeostasis). EPOC has been shown to increase fairly linearly with duration of exercise and exponentially with intensity of exercise as a percentage of VO2max.

First BeatEPOC

EPOC would seem a good candidate for a global measure of the load arising from an episode of training. The problem is it requires a training laboratory to measure it. It has been found however that EPOC can be predicted reasonably accurately from other measures. First Beat developed a method of predicting EPOC based on a prediction of %VO2max in turn based upon heart rate. It seems a little tenuous but the predicted correlation is not too bad with an R2 of 0.79. Not only that, but their is reasonable correlation between this and an older measure of intensity called TRIMP. Parts of this white paper are published.

Heart Rate Variability - HRV

Heart rate variability is the variation in the time interval between beats of the heart. It is an interesting if rather complex subject. It shows promise but as yet there is an insufficient evidence to prove its value in measuring training load. It is however being used as a recovery metric. The original and most direct way of obtaining HRV was with an electrocardiogram - ECG. This measures the electrical potential on the skin surface generated by the heart during its electrical cycle and plots it against time. It has a repeating pattern which includes a narrow upward spike in voltage termed the R wave which therefore defines a point in time. Heart rate variability is simply the variation in the time interval between successive R wave peaks. This variation is not however completely random but has a structure. This structure varies with time and activity. The study of heart rate variability is therefore complex requiring time, frequency or wavelet analysis.

HRV

One interesting way of looking at the self-similarity of HRV is by using a Poincaré plot.

Predicting Performance from Training Load

We have seen considerably varied methods of calculating the training load accumulated from a single workout. Although the general form of most seems in broad brush intuitively correct, more heavily weighting higher intensity activity, they appear rather ad-hoc and it is difficult to find supporting evidence. Some studies have even suggested that RPE might be superior! If we take a leap of faith and accept the validity of a single measure of training load, the next step is to use the calculated training loads to predict performance at any point in time. This is again not straightforward.

The Fitness and Fatigue Model

Yet again this was first developed by E Banister. It makes the assumption that a training load contributes to both fitness and fatigue. It also assumes that any accrued fitness or fatigue decay in an exponential fashion, with different half-lives for fitness and fatigue. Typically the half life for fitness 𝝀 is long at around 42 days and only 7 days for fatigue 𝜸. If we consider the fitness present immediately following a first episode of training at time t0 with load L0:

| fit(t0) = L0 |

but this fitness decays over time with half life 𝝀 so at time t after this single workout the accrued fitness remaining is:

| L0 × e-(t-t0)/𝝀 |

if we add in further training loads, the fitness is the sum of what is left remaining from each training load:

| fit(t) = L0 × e-(t-t0)/𝝀 + L1 × e-(t-t1)/𝝀 + L2 × e-(t-t2)/𝝀 etc... |

If the same is done for fatigue then performance is said to be:

| perf(t) = 𝛼 × fit(t) - 𝛽 × fat(t) |

The paper in the TRIMP link above shows good predictive behavior, but for only two athletes! I have found it difficult to find a really solid evidence base for performance prediction. Many of these algorithms are proprietary without a published evidence base in peer reviewed journals. I think they are a rough guide.

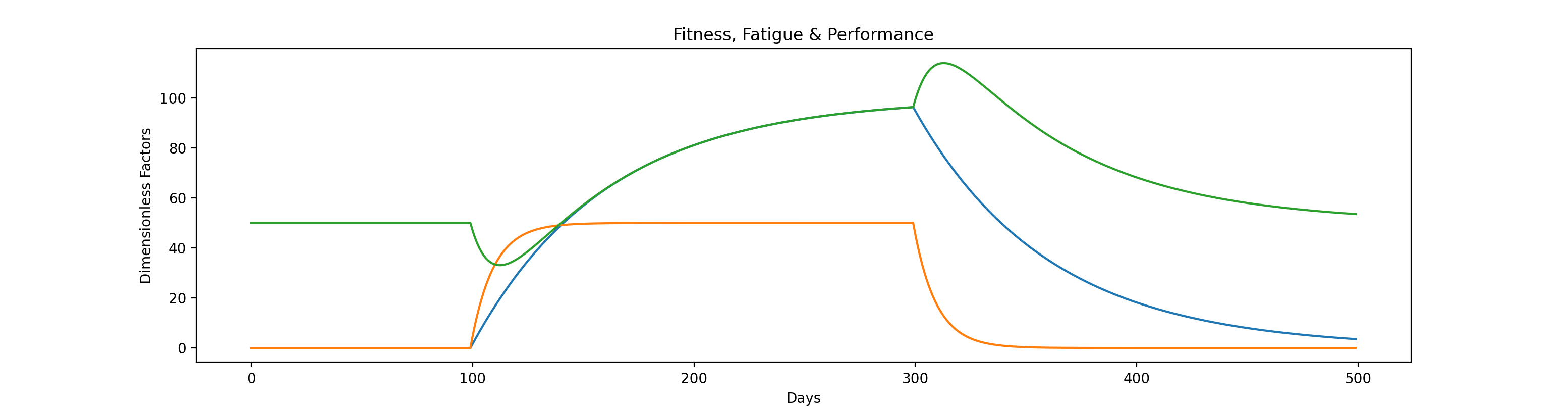

Here is one implementation of this model. I have used a half-life for fitness of 42 days, and 7 days for fatigue. I have scaled fitness so that with a steady daily (lets say TRIMP) of 100 the curve approaches 100 asymptomatically. I have scaled fatigue so with the same training stimulus it approaches 50. I have arbitrarily decided upon a baseline performance of 50 as this is never zero. Performance is the space in between. In this example training starts at day 100 and continues to day 300 after which training stops. Performance swings negatively as fatigue initially dominates over fitness. Fitness slowly catches up so that performance becomes positive (we expect training to improve performance long term). On stopping training fatigue decays more rapidly than fitness and we overshoot (the basis of tapering off before a race). Performance of course eventually declines to pre-training levels.

Although put together in a rather ad-hoc way, this model, in broad brush, captures what most athletes experience during an extended training cycle.

- The first run after a long pause is often a "honeymoon" run, better than expected.

- In the first week or so, performance actually deteriorates.

- Eventually we see improvement.

- Our improvement, with the same training impulses, reaches a steady state and we stop improving.

- When we stop (usually taper off) training our performance temporarily overshoots and we are ready to race.

- If we stop training our fitness will again decline back to its base level.

It is of course a gross simplification of training in which there are likely far more than two factors, fitness and fatigue. There are many similar models, many are proprietary and many do not have a published evidence base in peer reviewed journals. I think they can be a useful guide but should be combined with your own experience of what works for you.