Introduction

Once we move beyond subjective assessments of training intensity such as that suggested by Borg we are then presented with a new problem. What measure (or metric) should we use? Which is best? We shall see that there is no simple answer to this question as it depends so much on the context in which training takes place. A starting point is to merely list them before discussing their relative merits and limitations.

Pace

The following discussion does not include swimming. Water is a flat and viscosity limited environment. Pace is indisputably the best measure of training intensity.

Pace has to be the oldest and in many ways the most relevant. For a conventional race the winner is the person who takes the least time to cover a set distance. This means they have to have had the highest average speed during the race. This direct relationship to performance makes using pace understandable and intuitive. If we could measure pace with arbitrary accuracy and precision and all our training and racing were done on the flat it would be the simplest and I think the best measure. There are however some significant caveats:

-

Even a modest incline significantly affects the difficulty in maintaining a particular pace. Most of us do not run exclusively on the flat in training and competition. Hill training is an invaluable form of training (it should be taken judiciously like medicine) and allows us to develop a training intensity that is hard to achieve on the flat.

-

Measuring instantaneous pace reliably is not easy. The most common way to do this is by using the GPS in a sports watch but surprisingly, with conventional GPS accuracy, works very badly. The erratic instantaneous pace might to a certain extent be concealed from the user by using filtering but this then makes the pace value slow to respond to changes in pace. Foot pods, such as Stryd, provide a more accurate measurement of distance but more importantly allow accurate and precise pace measurement.

The problem with pace as an intensity measure on hills

Of course as runners we are aware of the effect of hills on speed. But what about running "on the flat". Imagine a 70kg runner with a rFTPw of 300 running at just under 40 minute 10k pace. He would cover 100 meters in around 25s and have produced 300 * 25 = 7,500 Joules of work over this distance. On a 2% gradient, say running on a road next to a rail track, he would have to produce an additional 2 * 70 * 10 = 1,400 Joules of work. This is nearly a fifth more work on what is really a modest gradient! We can see that in general pace is only going to be useful as a direct measure of intensity on the track.

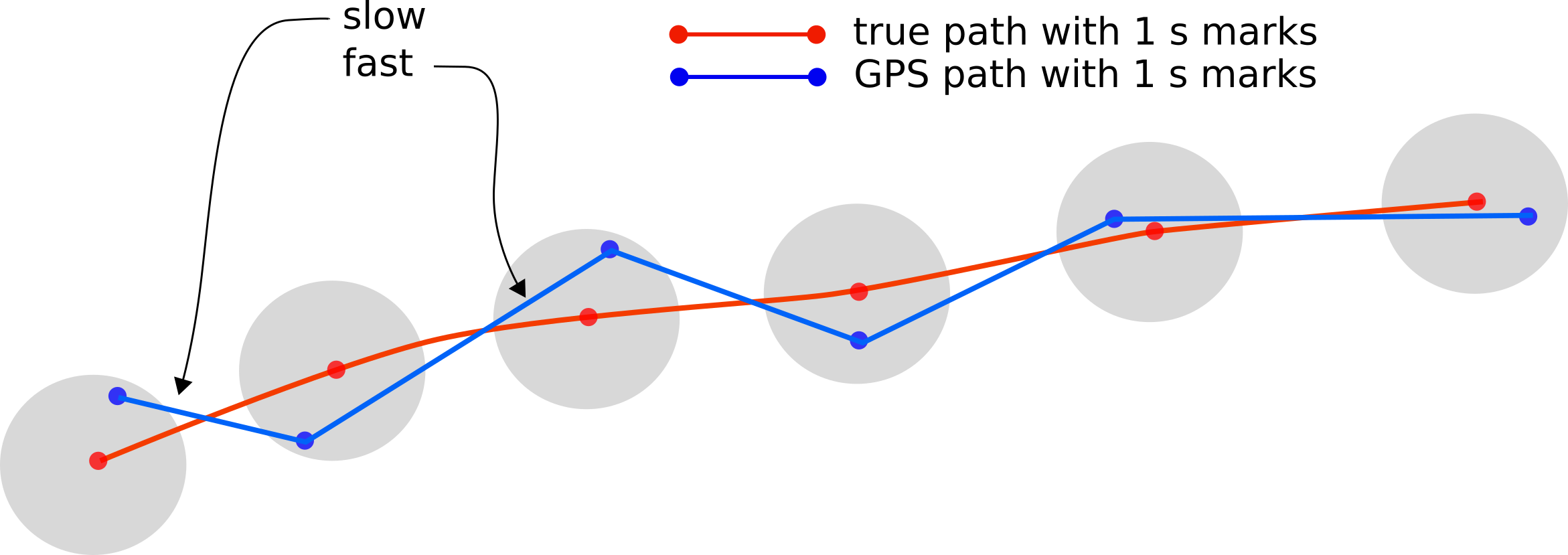

The problem with GPS instantaneous pace measurement

High resolution GPS typically samples every second. A problem arises because the GPS accuracy is limited to within a few meters (typically less then 3.5 meters) of your true location. Over an entire run this is virtually irrelevant. Over a one second period this is extremely relevant. Consider a runner with a 40 minute 10k pace running on average at just over 4 meters per second. The distance error of a single sample is of the same magnitude as the average distance traveled! Although clever algorithms disguise this problem using filtering (a simple example being a moving average over a several second window) this reduces the time responsiveness making it unsuitable for short intervals of under 30 seconds. Foot pods, such as Stryd, as well as providing highly accurate distance measurement, provide instantaneous pace with a level of accuracy and precision unachievable with conventional GPS.

Heart Rate

One can see the attraction of using heart rate as a measure of training intensity. It is a physiological measurement as opposed to an external measure of sport intensity such as pace or power. It is a single unambiguous measurable value which also has a gold standard for measurement, the ECG. It has been shown to have a reasonably linear relationship to exercise under many conditions.

Unfortunately this linearity is not maintained over the full spread of exercise durations and intensities. In particular, this relationship breaks down for short efforts (less than a couple of minutes), long efforts, and for exercise intensity above lactate threshold. Unfortunately these are serious limitations to its use in any program of polarized training.

Linearity/Dynamic range of heart rate response to increasing exercise intensity

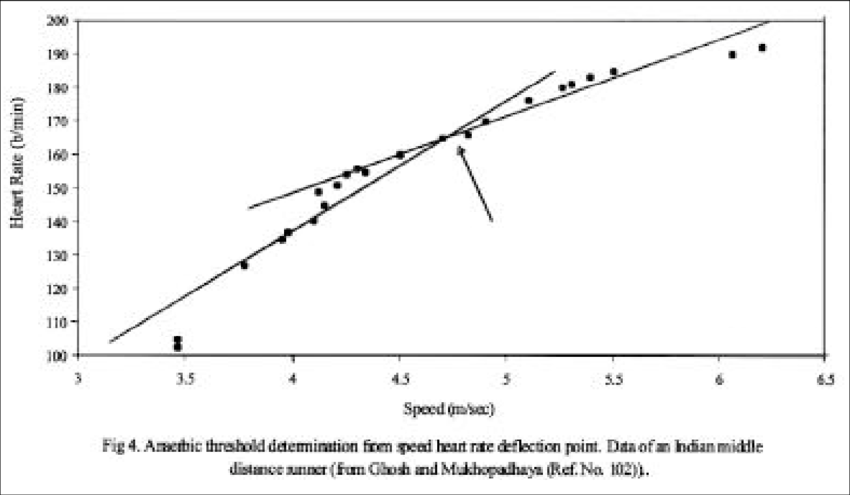

We all have a maximum heart rate. Mine is around 179. We might therefore expect a non-linear relationship to exercise intensity overall, perhaps with heart rate asymptotically approaching this limit. Despite this, below threshold, in many (not all) athletes, heart rate has an approximately linear response to increasing exercise intensity and this is where it can be most useful in guiding training. Common sense informs us that this relationship should eventually fail as intensity increases (something has got to give, and it does!). Conconi described a "deflection point", a correlation to lactate threshold and devised a field test based on this but opinion regarding its value is divided. Scatter plots of heart rate vs. intensity with a couple of lines superimposed on them "showing" the deflection point are wholly unconvincing. Perhaps the simplest description of the response is that it is curvilinear with a squashing up of heart rate values at higher intensities. This is clearly a problem for short interval training.

Responsiveness of heart rate to changes in exercise intensity

Heart rate takes time to respond to sudden changes in exercise intensity. Although there might be some small anticipatory change, it is in general playing catch-up, responding to the changing biochemistry and haemodynamics resulting from the change in exercise intensity. I personally find it takes around 20-30 seconds to respond, then at least 30 seconds to settle down after an interval. If the interval is shorter than a couple of minutes then this is not useful to me in guiding interval intensity.

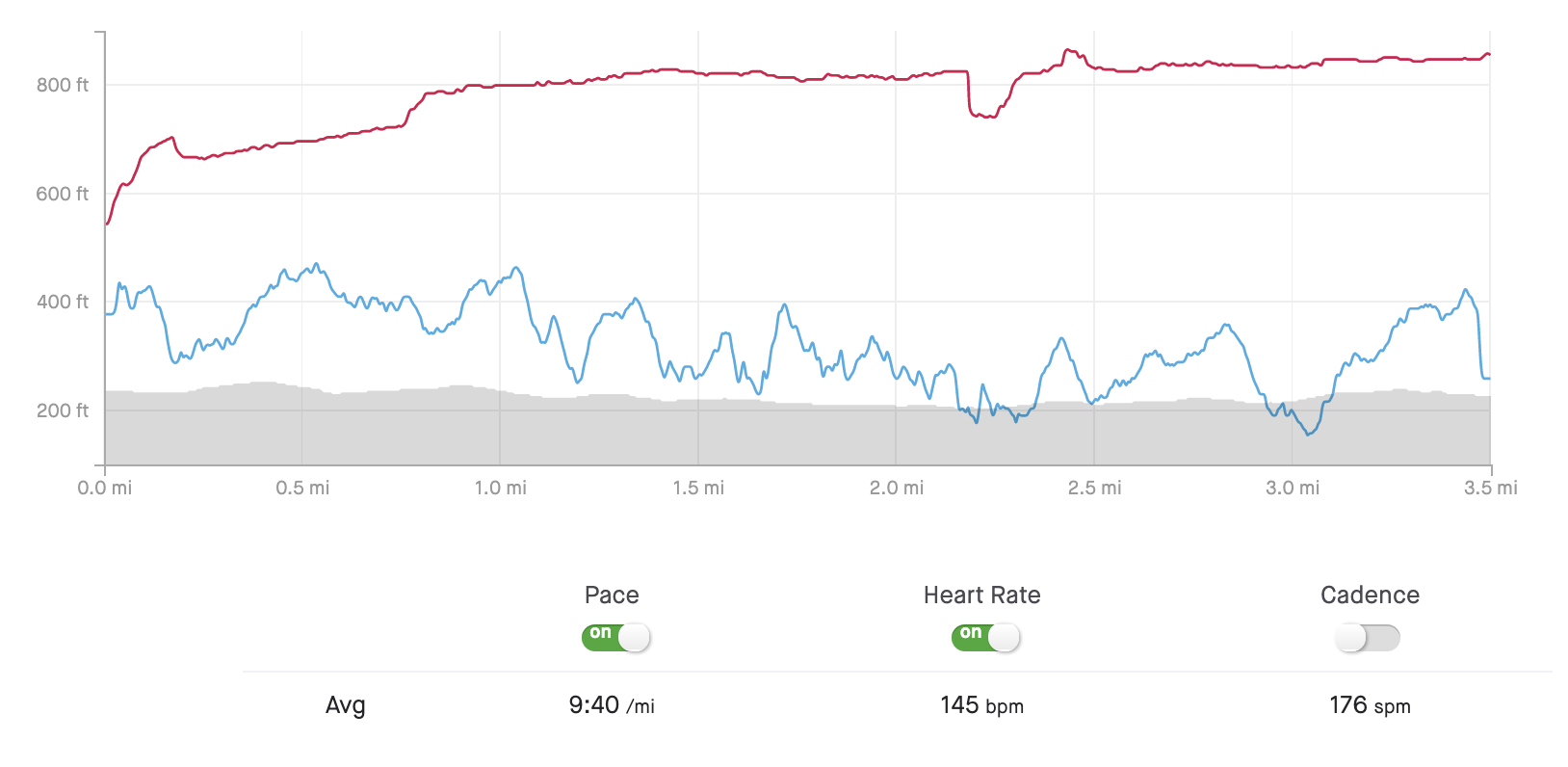

Slow upward drift in heart rate during exercise

OK, so there are significant limitations to the use of heart rate to guide interval training. But how good is it when running below threshold, perhaps on one of those long slow runs? Unfortunately heart rate rises slowly upwards while maintaining the same intensity (pace on the flat or power) over time. This becomes noticeable after a variable period of time ranging from 10 - 30 minutes of activity. (The image above shows one of my sorry efforts recorded in Strava in which heart rate increases despite pace falling during the run). On a 90 minute run the increase in heart rate at a constant effort might be as much as 15%. If you are exercising to a particular heart rate or heart rate zone, then your workout intensity will fall correspondingly over time. Ultimately you are left with heart rate only really being useful during recovery runs! I have to admit that I don't use heart rate to guide training intensity any more.

Other considerations regarding heart rate

Heart rate can be affected by a multitude of other things such as temperature, level of hydration and even ones psychological state. It is difficult to see how these could, systematically, be taken into account.

Some recreational athletes are reassured by having a heart rate value while exercising. This is fine but official advice (American Heart Association, British Heart Foundation) encourages the sedentary to do 150 minutes of moderate intensity activity per week and so provide guidance on heart rate values accordingly. This is clearly not going to applicable to people, at whatever level, who wish to compete. I don't believe it is possible, with good evidence, to say what is a "safe" heart rate. (I was amused to see one website say it is dangerous to exercise above your maximum heart rate! 🤣)

There are tiny risks during exercise that are more than offset by the long term health benefits.

So what is left? We will now discuss power, in particular contrasting cycling and running power

Power

Cycling Power

Power measurement has revolutionized cycling and is now widely used in structured training. This is not power measured at the back wheel (as would be the case of a car on a dynameter) but either at the crank or pedals. It is derived from the product of torque and angular velocity p = 𝜏 x 𝜔, and is the rotational analogue of the product of force and velocity. The calculated value results from basic physics and we can be confident that this is a true measurement of applied power. On the flat most of this power is utilized combating air and some road resistance. On gradients additional power is utilized increasing potential energy e = m x g x ∆h.

Cycling power has proved so popular because it overcomes the problems encountered using pace or heart rate as measures of intensity. It is not affected by gradient, does not squish up dynamic range at higher intensities and does not drift during a long cycling session. It responds almost instantly to changes in workout intensity. It is natural to ask is it possible to use running power as an intensity measure in running too. The answer to this question is not straightforward.

Running Power

Running power is really rather different to cycling power. Although we might wish to flatter ourselves, road and wind resistance make a comparatively small contribution to the work of running. Where is all this power going then? To understand where, we need to consider several things:

If you think of someone skating on ice, you see that simply translating in the horizontal plane should take very little power. If a skater stops applying any force then he/she will very slowly come to a halt as a result of losing their kinetic energy to friction and wind resistance. The potential energy of the skater remains constant. Cycling on an entirely flat surface at low speed is rather similar. The bike makes us so much more efficient.

Passive WalkerWe can also make completely passive mechanical walkers that utilize only inertia and a small downhill slope. These have an applied power of zero.

So why is running so energetically expensive? There is a clue when we strain but do no work at all. Imagine trying to push something really heavy, so heavy in fact that it does not move. We have applied a force over a period of time but without movement so no work is done. Our perception is very different! Although no physical work has been done, metabolic energy was used. But why? The reason is muscles use metabolic energy to generate tension, not work. This is profoundly important. Of course if the muscle is changing length this may correspond to work being done, but the metabolic cost is largely independent of movement. This is totally different to motors which use chemical or electrical energy to generate work.

We need to remember that although work is a scalar quantity, it can have a negative sign. When I push my supermarket trolley to get it moving I do positive work. When I slow it down to stop it crashing into my car I do negative work. Both activities consume metabolic energy because of how muscles work. Unfortunately muscles never get a free ride!

Think of someone jumping up and down on the spot. We have the same energy at the beginning and end of the activity. Overall very little physical work has been done. Little energy is needed combating air resistance and there is no external frictional resistance. An equal amount of positive and negative work is done. Our leg muscles generate positive work when we jump up and negative work when we land, both of which require the generation of muscle tension which in turn costs metabolic energy.

Now it is really easy to see why running on the flat costs a lot of metabolic energy yet does very little work. Running involves a cycle of both oscillating up and down and accelerating and decelerating. (There are other minor modes of reciprocal movement too). All of this activity requires the generation of muscle tension and so requires metabolic energy.

The Trick

So if we add up all the contributions to running power over a whole cadence cycle, what do we get? The element from wind resistance persists. The element from the change in altitude persists. The reciprocating power value, both positive and negative, cancels and so disappears from the sum. But on the flat or modest gradients the latter is the largest component of the sum! On the face of it, it looks like we are not going to be able to use power in running.

The trick is essentially one of accounting. It costs us metabolic energy to generate both positive and negative power. If we ignore the sign of the power it relates to metabolic cost. This is the crux of the controversy over power. It is clearly not a true measure of applied power in the same way as cycling power is, but it does represent the metabolic cost of running in the same way that cycling power does. The details of how this accountancy "fix" is achieved differ from device to device with no industry standardization. This means that, in general, it is not possible to compare power values from different devices. We must view the Wattage values displayed merely as relative measures of running intensity.

Is running power any good?

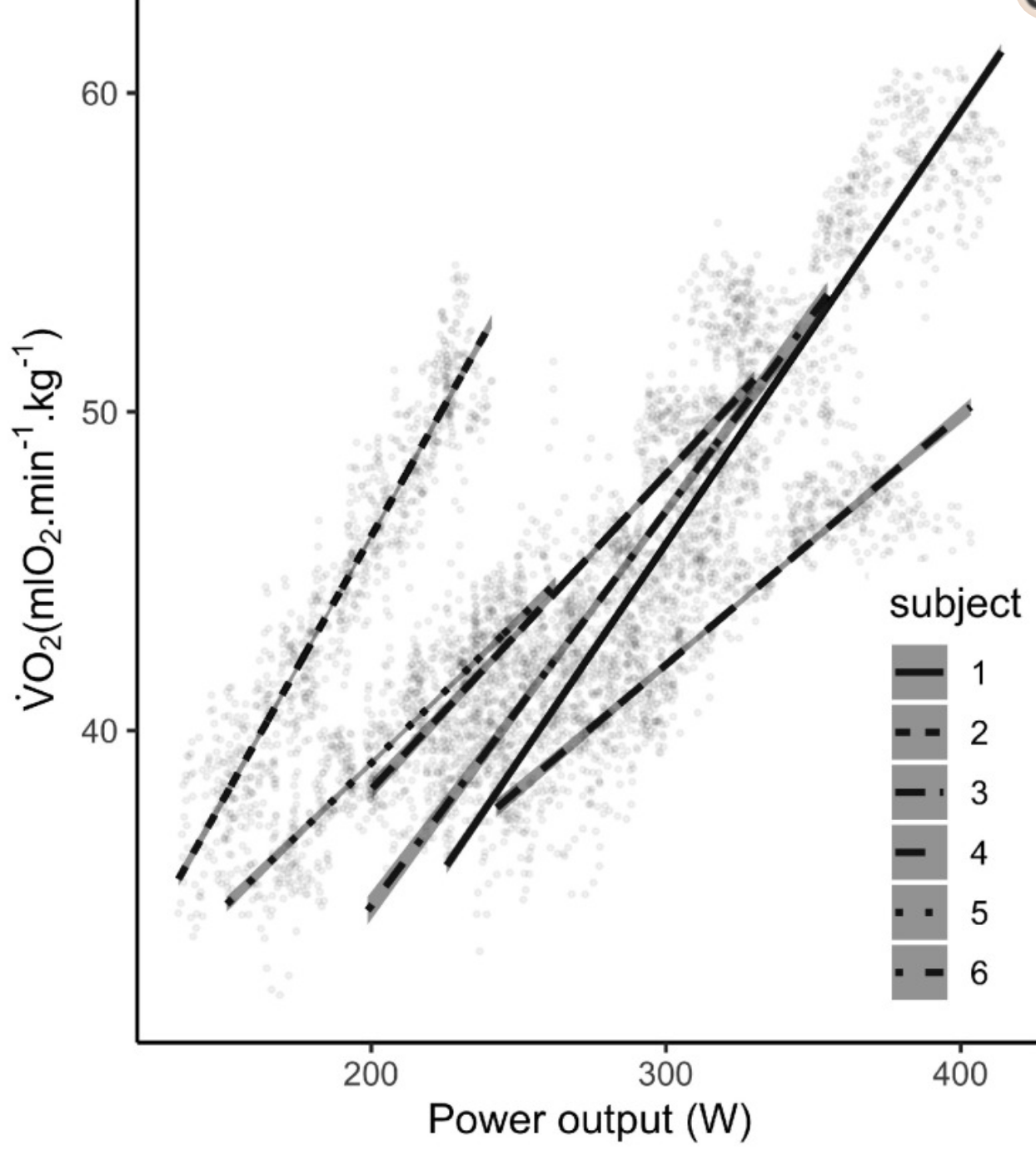

Heck yes! Despite it not being a true measure of applied power, it is a true representation of running intensity independently validated against VO2 and is revolutionizing structured training in running just as it did in cycling. It is useful across the full gamut of training, long slow runs, short intervals, threshold runs, on the track, up hills etc... We do not need to use more than one measure depending on circumstances. This is enormously valuable and allows us to effortlessly collect information from the whole of our training to inform our training plan through calculations of training stress. There is no need to try to inter-convert (guestimate) different measures (such as pace on the track and heart rate on a hilly slow run)

Is it the perfect solution?

Sports (Basel)2020 Jul; 8(7): 103

Not yet. If not a true measure of applied power, what does the displayed value, optimistically shown in Watts, really mean? There is no industry standardization and so power readings vary a lot from one device to another. Thankfully they are on the whole consistent with each other (mathematically we would describe the relationship as affine) This means we have to consistently use a particular device to avoid polluting our power data set.

Power and Gradient Adjusted Pace

It would be straightforward to measure running pace and power on the flat and construct a curve (it is a near linear relationship) so as to display a power equivalent flat running pace. This automatically standardizes the value and makes more intuitive sense to most. I suspect this is not done because it would be difficult to distinguish this, from a marketing point of view, from existing crude gradient adjusted pace values. I personally would like to see this.

A bit more detail for the more heroic athlete!

This discussion is a very simplified overview of running power. Running power is so much more complicated than cycling power. Negative work may be less metabolic energy consuming than positive work. Not all force is generated by muscle as we do get a bit of a free ride from the elasticity of some tissues such as the ileotibial band and plantar fascia. What equations should we use? Stryd says their running power is p = F ⦁ V where F is the applied force and V the velocity of the center of mass of the athlete. The acceleration of the center of mass, from Newton's second law, is proportional to the applied force so we can rewrite this as p = m A ⦁ V where m is the mass of the athlete and A the acceleration of the center of gravity. If we calculated the time integral of this periodic power value over an entire run it would be zero! (wind resistance merely contributes another force affecting A so this true element of work by the athlete is not captured) What really happens is p = m | A ⦁ V | is used in calculating running power. Of course the pod is not attached to the athlete's center of mass. If attached to the body (first Stryd combined hrm and power pod) then there is a fairly fixed offset which does not affect A so not an issue. Measuring power from the foot or wrist really is something else. For the Stryd foot pod, repeated treadmill measurements have shown it is possible to reliably predict the acceleration of the center of mass and this model is used to allow their foot pod to measure running power. This may seem a stretch but they are confident enough, unlike most other manufacturers, to publish their data which shows this to be the case.

Summary

No affordable portable sensor provides us with a measure of work intensity in terms of how much metabolic power is required. In a laboratory we can of course measure VO2 which, over and above VO2 at rest and below VO2max will inform us of the required metabolic power and this forms our gold standard of measurement. This has been used to validate running power measurements including Stryd's foot pod. The earliest and most common methods of measurement (pace and heart rate) are of use but only over a relatively limited range of training situations. If we use more than one method in an attempt to overcome these limitations (say using pace on a track and heart rate on medium duration sub-threshold run) then we have the problem of how to compare and integrate these into our training data. Even if we do use more than one, they are still not appropriate to all training situations in a polarized training program. Running power is applicable to the vast majority of training. We do have to ensure we use a consistent source of power data if we are not to corrupt our power data set as there is no universal standard for running power, the values of which differ between the sensors of different manufacturers.

The following table outlines the limitations of various running intensity sensors:

| Measure | Responsive | Drift Free | Gradient Independent | Device Independent | Wind Independent |

| Pace | YES | YES | NO | YES | NO |

| HR | NO | NO | NO | YES | YES |

| Power | YES | YES | YES | NO | SOME DEVICES |

| Power GAP | YES | YES | YES | YES | SOME DEVICES |

The Bottom Line

Running power is now readily available on many devices. Unfortunately it is not in the commercial interest of companies implementing running power to agree upon a common standard. Clearly the best option is to convert any proprietary power number to a common currency, power based gradient adjusted pace. We might call this pGAP. Doing so and adopting pGAP would make data from different devices comparable and understandable. pGAP on a running track without wind would however merely be pace and the marketing bubble might burst!

The end result is that if runners are not careful, their running power data sets will be polluted by significantly different values from different devices (e.g. wrist based power on a Garmin watch vs. Stryd) and any analysis based on these mixed data sets worthless.